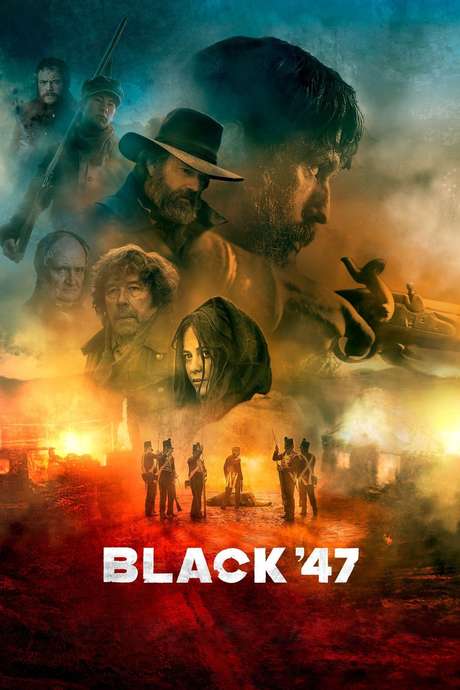

What’s Black ‘47 about?

Set in the worst year of the Irish famine, 1847, Black ‘47 relates a tale of a young soldier, Martin Feeney, returning home from British wars in Afghanistan and India to find his family dead or almost dead, and his country in ruins. He sets out to avenge his losses, resulting in highly entertaining fight scenes. They don’t show everything, either by dint of dim lighting or simply cutting to the next scene, but they’re satisfyingly violent and often sudden.

Feeney isn’t just any foot soldier of the mighty British Army. He’s an Irish Ranger – highly skilled in the application of death, much of which he learned from the tribesmen of Afghanistan - and he’s deserted the army of his English overlords. He’s a rebel with a powerful cause, one that he knew nothing about until he went home. He can’t set anything right, even while he takes revenge, but he can do his tiny part and it’s well worth a view.

What’s special about it?

What seems to have passed by the young, male, English reviewers of various film magazine sites, is the endorsement of the telling of this story by Irish arts organisations. This is an Irish film (despite its Australian lead), telling an Irish story, with much of it in the Irish language. (Gaeilge, or Irish in English, not ‘Gaelic’, thanks, Empire Online).

The ruling classes, including Captain Pope and Lord Kilmichael, are English, not ‘Brits’. They’re ‘one-note of evil’ in the film (yes, quote taken from the stupefying review on Empire), because that would be all that the starving Irish people would have seen of them. Evil. Condescending. Unempathetic. Caricatures of rich people. It’s kind of the point of the film.

The underlying story of the famine isn’t ‘just’ the suffering of the Irish people due to an inevitable natural disaster brought on by a series of poor harvests. It’s the fact that the horrific tragedy wasn’t inevitable at all. Exports of foodstuffs from Ireland to England during the famine increased, with 4,000 ships carrying edibles in 1847 while 400,000 Irish people starved to death or died of related causes.

This is an important film because it shows a part of history from a point of view that isn’t taught in British schools. Many of us in England and the US have Irish forebears, and many of them will have emigrated at the time of the famine. The popularist view that the British Empire is an institution to be proud of is shown to be twaddle in the face of what amounts to an attempt at genocide in one of England’s neighbouring countries. In the film, Lord Kilmichael (Jim Broadbent) states that it is to be hoped that after the famine there will not be one Celtic Irish person left in the land. Black ‘47 is a stark reminder that ordinary people have never had anything from the English government that they didn’t die for.

As mentioned at the start, it’s the details of this movie that make it special, and they’re shown, not told. The anglicisation of Irish names given in the Protestant tent as the people wait for the minister to stop waffling scripture so that they can eventually eat, giving up their very names for the sake of not starving to death. The fact that the landlord’s tax was paid in lives, when roofs were removed from houses leaving starving people to die from exposure. The dozens of trinkets and ornaments in the tax collector’s home, because he’d been a willing party – a collaborator – to the losses of so many people. The scene in the courtroom as the judge takes gladness in convicting a man to transportation for speaking his own language - reminiscent of the way in which the speaking of the Welsh language in Wales was outlawed also by the English. (See why calling them Brits is just plain wrong?)

Who are the important characters?

Well, everyone in the movie is crucial to the message. If anything, they underact, but there are some excellent performances.

At the top of the billing, you’ve got Hugo Weaving, acting his heart out as Inspector Hannah. He’s a drunk, a broken, hard-to-like man – likely with PTSD from his years fighting for the British in Afghanistan and the East. His judgement is shot and he’s condemned to hang for murdering a suspect connected to the Young Irelanders. It turns out not only did he fight with Martin Feeney in Afghanistan, but Feeney saved his life during an ambush near Kabul. For this reason, Hannah struggles on a moral level with tracking and capturing Feeney.

Alongside Weaving, stands James Frecheville as Martin Feeney. A hollow man he is not, although his demeanour is almost impenetrable. Still waters run deep, my friend, and he’s got more than a smidgen of empathy and moral compass.

Ellie (Sarah Greene) is Martin’s sister in law. She and her children – including her strong and angry son – represent the dispossessed left to ferret for scraps of nothing in the face of English cruelty. So many thousands of people were lost in the same way, through no fault of their own, and yet blamed for their own demise by their English overlords in distant Westminster.

Hobson (Barry Keoghan), the young private accompanying the posh-boy Captain Pope (Freddie Fox) and Inspector Hannah in their search for Feeney, is perhaps my favourite character. His growing understanding of the wider political situation is sweet and grim, and culminates in a disastrous attempt to do the right thing in the face of unabated cruelty.

Conneely, played by Stephen Rea, is a complex character too. His almost Shakespearian fool is as smart as he is witty, as cunning as he is wise. He speaks English, so offers to interpret for Captain Pope early on in the tale and refuses to leave later on so that the tale might ‘accurately be retold in the future’, an allusion to the loss of Irish folklore during the famine. Later, chatting with Lord Kilmichael in the inn, he’s sharp and just short of outspoken. He says things that no-one else would have got away with. He’s in a privileged position and it’s beautifully used.

Will you like it?

Just on a simple level, this is a well-rendered genre Western with muskets and scary-looking knives. The fight scenes are tense, partly due to the fact it takes a terrifying amount of time to reload a musket, and the violence is largely satisfying.

If you’re looking for a movie with a bit more to say than ‘Bad guys bad, good guys good’, this could also be your bag. One of the few films out there set during the Irish Famine, it puts the personal tale first but doesn’t skimp on showing the viewer the wider story. It doesn’t sacrifice story for action or for political message, but gives a horrifying backdrop to a well-executed genre film.

What can you read for more background on the Irish Famine?

If you’ve heard of the Irish Famine, but you didn’t have any real understanding of what it meant, you might find Rev. John O'Rourke's The History of the Great Irish Famine of 1847 available at Project Gutenberg. It's old, but highly readable and fascinating, a brilliant and frank account of dark politics and opportunism by powerful people. Also, free to own.

A shorter, more modern piece to check out is The Story of the Great Irish Famine by Michael B. Roberts to be found on Kobo for £0.86. Running only to about 9000 words, it looks at the role of politics and what could have been done to relieve the suffering of so many people.

For a classic fictional account of an earlier Irish famine, the classic The Black Prophet: A Tale of Irish Famine by William Carleton is also available free via Project Gutenberg, though you can pick up a copy at Kobo for £0.79.

Black ‘47 is no longer available to watch on Netflix, but is well worth buying on DVD to keep.